FOTOTECA SIRACUSANA

PHOTOGALLERY - FOTOGRAFIA VINTAGE - BIBLIOTECA TEMATICA - CAMERA OSCURA B&W - DIDATTICA

SCRIPTPHOTOGRAPHY

John LOENGRAD (USA)

JOHN LOENGARD

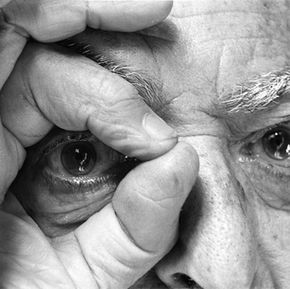

Ha detto Henri Cartier-Bresson, che tra l’altro vediamo qui in alcuni scatti, che niente è «più fugace d’una espressione che passa su un viso». In quella piccola biografia scritta sul volto di una persona, e che il fotografo cerca di riassumere nei suoi scatti, tracima un interrogativo, un dilemma – lo stesso – che in letteratura attraversa il racconto biografico e che ruota intorno a una scelta prospettica. Entrambi, scrittore e fotografo, in definitiva sono accomunati nell’ingaggio d’una sfida. Non c’è dubbio che lo scrittore abbia sul fotografo l’indiscusso primato di una trattazione più estesa, che si dispiega in ognuna delle pagine del suo libro e nel quale ci introduce inesorabilmente nella vita del protagonista. Al fotografo non è data la stessa occasione: il fotografo non scrive, vede. Ed è una responsabilità assai più grande, perché quanto vede oltre l’obiettivo, è destinato all’incorruttibile dimensione dell’eterno, a un tempo che non è più tempo. La consapevolezza della supremazia dell’immagine sulle parole, obbliga il fotografo a infoltire di significato quanto risiede “dentro” il ritratto, a provare cioè di fermare e dare forma plastica a quel portato d’esperienze che abita nella forma dell’uomo, oltre la sua stessa esistenza, perché questi diventi uno “specchio dotato di memoria”. Raccontare con uno o più scatti l’essenza di una persona è dunque una sfida suprema. John Loengard, lontano dalla celebrazione tout-court del primo piano, non cade nelle insidie del genere. La sua ritrattistica è riassuntiva. Un dettaglio, un gesto, un vezzo sono chiamati alla narrazione del tutto, all’esplicitazione cioè di talenti colti ora nella conclamazione d’un gesto ora nel loro intrinseco oggettivo. Loengard conosce i suoi soggetti. Li conosce e li ammira. Questo accorcia le distanze e allo stesso tempo, nella fondazione di una complicità, vediamo come l’afflato tra fotografo e ritratto arrivi all’osservatore con la sincerità d’una confessione. Alcuni scatti sono molto conosciuti. Il ritratto di Brassaï concentra la nostra attenzione sulla mano che chiude l’occhio come un obiettivo; e lui, Brassaï, “l’occhio di Parigi”, com’è stato definito, sta al gioco in una riuscita connessione di rimandi. Una parte per il tutto, e citazioni di natura fisica. Ancora mani, quelle di Georgia O’Keeffe, come se verso le stesse, le lunghe, sinuose, sensuali ritratte da Stieglitz si andasse in pellegrinaggio, con una inestinguibile devozione. Basta una pietra nera sul palmo ed ecco svelata l’incontenibile passione dell’artista per i sassi, in un gesto intimo pari a quello di Louis Armstrong mentre protegge le labbra applicando uno strato di balsamo. Poi c’è il nume. Sua Maestà, il fotografo che per molti è Dio e Mosè insieme: Henri Cartier-Bresson. Lui c’è senza esserci. Si ritrae, risponde alla foto con una foto, intessendo con l’amico il gioco dell’inganno. Cartier-Bresson, che nei ritratti amava carpire il silenzio interiore, lui, per sé, li detestava. Ora è di fronte a Loengard, l’aria è quella della rilassata conversazione tra amici che si stimano, con la luce d’un pomeriggio parigino che invade l’abitazione di Dio. Più in là non va, non si concede, non si può: oltre è il territorio del sacro, il Sancta Sanctorum della sua volontà. Ma Loengard è abile e sa che anche agli dèi succede di giocare talvolta e dunque è lì, pronto a immortalare Cartier-Bresson mentre insegue come un bambino le acrobazie d’un aquilone. C’è più intimità in questa fotografia che in ogni altra. Loengard, predilige un punto di vista laterale, una prospettiva riassuntiva nella quale diramare l’essenza del personaggio. Nelle sue fotografie si avverte come la scelta compositiva giochi un ruolo fondamentale nel tentativo di descrivere il soggetto. Lo dimostra la foto che ritrae Annie Leibovitz, dove l’arditezza della fotografa è pari alla sua libertà intellettuale e professionale; mentre Allen Ginsberg, che guarda l’obiettivo, è assorto in una nuvola pensosa e densa che ne confonde i tratti. Ognuno ha la sua cifra, ognuno sembra immerso dentro la propria specifica essenza. Così Merce Cunningham, ballerino e coreografo, in un momento delle prove sembra essere il solo in asse in un ambiente di triangoli e rigide prospettive in un campo profondo come il suo talento. Loengard ritrae il silenzioso mistero del genio, d’ognuno cattura un lato, una peculiarità, un tratto che racchiuda in sé la chiave per raccontare. Fotografare comporta responsabilità verso i soggetti, un clic sbagliato e la persona che si ha davanti diventa qualcosa d’altro, estraneo persino a se stesso, come uno specchio svuotato della memoria.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

foto John Loengard

Henri Cartier-Bresson said (we see here in some shots) that nothing is «more fleeting than an expression that passes on a face». In that small biography written on a person's face, and which the photographer tries to summarize in his shots, overflows a question, a dilemma - the same - that in literature goes through the biographical story and that revolves around a perspective choice. Both, writer and photographer, are ultimately united in the engagement of a challenge. There’s no doubt that the writer has the undisputed primacy of a more extensive treatment over the photographer, which unfolds in each of the pages of his book and in which he introduces us inexorably into the life of the protagonist. The photographer is not given the same opportunity: the photographer doesn’t write, he sees. And it is a much greater responsibility, because what is beyond the objective is destined for the incorruptible dimension of the eternal, in a time that is no longer time. The awareness of the supremacy of the image over words, obliges the photographer to give meaning to what is "inside" the portrait, that is, to try to stop and give plastic form to that result of experiences that lives in the form of man, beyond the its very existence, because these become a "mirror with memory". Telling the essence of a person with one or more shots is therefore a supreme challenge. John Loengard, far from the tout-court celebration of the first floor, doesn’t fall into the pitfalls of this kind. His portraiture is summary. A detail, a gesture, a habit are called to the narration of the whole, that is to say, to the explanation of talents caught now in the proclamation of a gesture now in their objective intrinsic. Loengard knows his subjects. He knows them and admires them. This shortens the distances and at the same time, in the foundation of a complicity, we see how the afflatus between photographer and portrait arrives at the observer with the sincerity of a confession. Some shots are well known. Brassaï's portrait focuses our attention on the hand that closes the eye like a target; and he, Brassaï, "the eye of Paris", as it has been defined, is at stake in a successful connection of references. A part for the whole, and physical quotes. Still hands, those of Georgia O'Keeffe, as if towards them, the long, sinuous, sensual portraits of Stieglitz went on pilgrimage, with an unquenchable devotion. A black stone on the palm is enough and the artist's uncontainable passion for stones is revealed, in an intimate gesture equal to that of Louis Armstrong while protecting the lips by applying a layer of balm. Then there is the nume. His Majesty, the photographer who for many is God and Moses together: Henri Cartier-Bresson. He is there without being there. He retracts, responds to the photo with a photo, weaving the game of deception with his friend. Cartier-Bresson, who in portraits loved to seize the inner silence, he, for himself, hated them. Now he is in front of Loengard, the air is that of the relaxed conversation between friends who esteem each other, with the light of a Parisian afternoon invading God's house. He doesn’t go further, he doesn’t allow himself, he cannot: beyond the sacred territory, the Sancta Sanctorum of his will. But Loengard is skilled and knows that even the gods happen to play sometimes and therefore he is there, ready to immortalize Cartier-Bresson while chasing the stunts of a kite like a child. There is more intimacy in this photograph than in any other. Loengard prefers a lateral point of view, a summary perspective in which to branch out the essence of the character. In his photographs, one senses how the compositional choice plays a fundamental role in the attempt to describe the subject. In his photographs, one senses how the compositional choice plays a fundamental role in the attempt to describe the subject. This is demonstrated by the photo that portrays Annie Leibovitz, where the boldness of the photographer is equal to her intellectual and professional freedom; while Allen Ginsberg, who looks at the lens, is absorbed in a thoughtful and dense cloud that confuses his features. Each has its own figure, each seems immersed in its own specific essence. So Merce Cunningham, dancer and choreographer, at a time of rehearsals seems to be the only one on the axis in an environment of triangles and rigid perspectives in a field as deep as his talent. Loengard portrays the silent mystery of genius, each one capturing a side, a peculiarity, a trait that contains the key to tell. Photographing involves responsibility towards the subjects, a wrong click and the person in front of you becomes something else, even alien to himself, like a mirror without memory.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

ph. John Loengard