FOTOTECA SIRACUSANA

PHOTOGALLERY - FOTOGRAFIA VINTAGE - BIBLIOTECA TEMATICA - CAMERA OSCURA B&W - DIDATTICA

SCRIPTPHOTOGRAPHY

David LACHAPELLE - 1 (USA)

DAVID LACHAPELLE

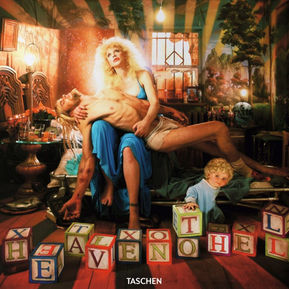

Se l’Apocalisse è questa non possiamo che attenderla a braccia aperte. Coloratissima, eccessiva, strabordante e neo barocca; tutto declinato in un super-pop postmoderno in cui le tonalità punch illuminano ambientazioni lucenti come stagnola di caramelle e soggetti di ogni estrazione cui è restituito un protagonismo risarcitorio. Ma non chiamatelo blasfemo, è David LaChapelle.

Nato dalle viscere della comunicazione pubblicitaria e di uno star system autocelebrativo desideroso di una rilettura di se stesso, LaChapelle intuisce la sterzata iconica da imprimere alle sue opere. E tutto diviene eccessivo ma intuibile, misterioso e intellegibile. Come la sua formazione. Contrariamente a chi reputa destrutturante il suo lavoro, noi non cogliamo iconoclastia: il suo “Last supper”, citazione del più celebre capolavoro di Leonardo Da Vinci, ha una sacralità postmoderna da cogliere nelle fattezze dei commensali, apostoli della contemporaneità reclutati anch’essi tra il numero degli ultimi. Né ci scandalizza (al contrario, la amiamo) la sua personalissima versione della ‘Pietà’ michelangiolesca – non sarà il solo omaggio al grande maestro – nella quale a un Cristo appena deposto scorgiamo tra le braccia i segni di una passione privata e distruttiva. E’ stato in visita in Italia LaChapelle, ha amato i grandi maestri, si vede e vuol dircelo. Le sue versioni di ‘The deluge’ e la ‘Rebirth of Venus’ altro non sono che due doverosissimi omaggi, quasi due “d’après”, a Michelangelo – di cui copia l’allestimento nella Cappella Sistina – e a Botticelli, forse un precursore, di certo un ispiratore, come Rodin e Blake. Corporeità e lirismo che dialogano con il più allucinato e riuscito dei sogni, con allucinazioni psichedeliche ora surrealiste ora somiglianti a un circo di creature libere e anarchiche non rispondenti a nessun assioma borghese. In LaChapelle la fotografia è mezzo assoluto, al pari di una tavolozza per un pittore. E nei grandi formati delle sue opere aleggia come un ‘orror vacui’ da colmare appena possibile, in fretta, con un moto pressoché compulsivo, perché tutto – ma proprio tutto – sia detto senza omissione di dettagli. Di lui è stato detto che è “il Fellini della fotografia” e noi non possiamo che concordare perché in comune con il grande regista LaChapelle ha una dote assoluta: l’ironia. E dove c’è ironia c’è leggerezza. E non manca neanche nelle fotografie che affrontano temi escatologici come la morte. In ‘What will you wear when you’re dead’, affronta l’annosissimo (e mai risolto) tema della fine dell’anima; esiste una nuova vita oltre la morte? Chi lo sa. Però è conveniente presentarsi bene una volta nell’Aldilà. Riletture, dissacranti ma probabili. E attuali: un Gulliver è tenuto prigioniero non più da sospettosi Lillipuziani ma da un folto numero di bamboline determinate a tenere il malcapitato oggetto di una rivincita di genere.

Fasti. E feste, dove la temporaneità corrobora il consumo e nei quali aleggia la consapevolezza di un tempo che sta per terminare, forse per sempre e per cui bisogna affrettarsi a godere. Più tardi potrebbe essere fatale e a dirlo sono i ritratti di donne coloratissime sopravvissute a una distruzione post-atomica, a un disastro che ha lasciato intatti gli umani che ma che ha distrutto quanto da lui è stato creato. E quello che ha creato è talmente brutto che per gradirlo serve una lettura caricaturale, anch’essa eccessiva e coloratissima. Ecco che le raffinerie, nello sforzo di una ‘digestione forzata’ divengono totemiche e spettrali ma che, sebbene ricostruite in studio con materiali riciclati, non perdono per nulla la loro bellicosità.

David LaChapelle è un genio della comunicazione visiva. E come tutti i geni si dimostra poco interessato alla verità se non come luogo nel quale imbastire una lunga vertigine onirica, in cui il sogno si dimostra più vero del vero, nel segno di un super-pop di rare efficacia e bellezza.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

foto David LaChapelle

If the Apocalypse is this we can only wait for it with open arms. Colorful, excessive, overflowing and neo-baroque; all declined in a postmodern super-pop in which the punch shades illuminate bright settings such as candy foil and subjects from all backgrounds who are given a compensatory protagonism. But don't call him blasphemous, it's David LaChapelle.

Born from the bowels of advertising communication and a self-celebrating star system eager for a rereading of itself, LaChapelle senses the iconic steering to impress on his works. And everything becomes excessive but intuitive, mysterious and intelligible. Like his training. Contrary to those who consider his work destructuring, we do not take iconoclasm: his "Last supper", a quote from the most famous masterpiece by Leonardo Da Vinci, has a postmodern sacredness to be grasped in the features of the guests, contemporary apostles also recruited from among the number of the last. Nor does it offend us (on the contrary, we love it) his very personal version of Michelangelo's 'Pietà' - it will not be the only homage to the great master - in which we can see the signs of a private and destructive passion in the arms of a newly deposed Christ. LaChapelle has been visiting Italy, he has loved the great masters, he sees himself and wants to tell us. His versions of 'The deluge' and the 'Rebirth of Venus' are nothing more than two dutiful homages, almost two "d'après", to Michelangelo - whose installation he copies in the Sistine Chapel - and to Botticelli, perhaps a precursor. , certainly an inspirer, like Rodin and Blake. Corporeality and lyricism that dialogue with the most hallucinated and successful of dreams, with psychedelic hallucinations now surrealist now resembling a circus of free and anarchist creatures not responding to any bourgeois axiom. In LaChapelle photography is an absolute medium, like a palette for a painter. And in the large formats of his works he hovers like a 'horrible vacuo' to be filled as soon as possible, in a hurry, with an almost compulsive motion, so that everything - absolutely everything - is said without omitting details. It has been said of him that he is "the Fellini of photography" and we can only agree because in common with the great director LaChapelle he has an absolute talent: irony. And where there is irony there is lightness. And it is not lacking in photographs that deal with eschatological themes such as death. In 'What will you wear when you're dead', he tackles the age-old (and never resolved) theme of the end of the soul; is there a new life beyond death? Who knows. But it is convenient to present yourself well once in the Afterlife. Re-reading, irreverent but probable. And current: a Gulliver is held captive no longer by suspicious Lilliputians but by a large number of dolls determined to keep the victim unfortunate subject to a gender revenge. Glories. And parties, where temporariness corroborates consumption and in which the awareness of a time that is about to end, perhaps forever and for which we must hurry to enjoy. Later it could be fatal and to say are the portraits of colorful women who survived a post-atomic destruction, a disaster that left humans intact but that destroyed what he created. And what he created is so bad that to appreciate it, you need a caricatural reading, which is also excessive and colorful. Here the refineries, in the effort of a 'forced digestion', become totemic and spectral but which, although rebuilt in the studio with recycled materials, do not lose their bellicosity at all.

David LaChapelle is a genius of visual communication. And like all geniuses, he shows little interest in the truth except as a place in which to base a long dreamlike vertigo, where the dream proves more true than truth, in the sign of a super-pop of rare efficacy and beauty.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

ph. David LaChapelle