FOTOTECA SIRACUSANA

PHOTOGALLERY - FOTOGRAFIA VINTAGE - BIBLIOTECA TEMATICA - CAMERA OSCURA B&W - DIDATTICA

SCRIPTPHOTOGRAPHY

PETER HUJAR

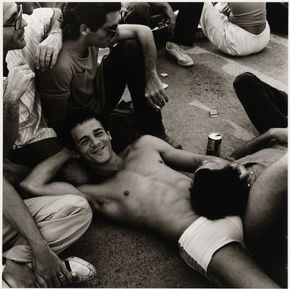

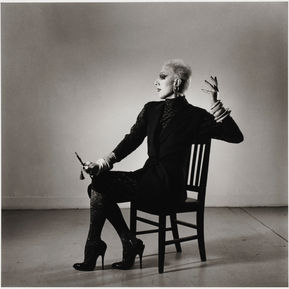

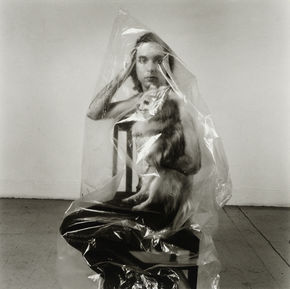

1976, esce “Portraits in Life and Death”. Un libro insolito, una magistrale sequenza di ritratti è seguita da una serie di immagini di mummie custodite a Palermo, nelle catacombe del Convento dei Cappuccini, meta di molti fotografi americani che vi si recano con il medesimo approccio del Grand Tour. Forse è per questo che nella prefazione al libro Susan Sontag scrive “La fotografia trasforma il mondo intero in un cimiteri”, prefigurando uno dei temi chiave dell’opera di Barthes. Lui, il fotografo americano, talentuoso quanto misconosciuto è Peter Hujar (1934-1987) e nell’ambiente degli addetti ai lavori è considerato uno dei più influenti fotografi della fine del XX secolo. Schivo, riservato e coerente Hujar non amava i compromessi né ebbe mai un rapporto funzionante con galleristi e collezionisti. Si direbbe un outsider, ma Hujar è riuscito a influenzare il lavoro di molti celebri colleghi che dalle sue fotografie hanno trovato ispirazione. Ma le influenze finiscono qui, sicché gli omaggi di Goldin e Mapplethorpe vengono rispediti al mittente senza tanti complimenti e con l’invito di Hujar a non essere citato come fonte ispiratrice. A Nan Goldin rimproverava certe derive commerciali, alla strizzatina d’occhio a un manierismo autoreferenziale; peggio andò a Mapplethorpe, accusato di mostrarsi troppo interessato alla costruzione di un pubblico adorante, e che il desiderio di voler fare ingresso nei musei avesse evaporato la portata eversive delle prime fotografie per fondare una specie di neo classicismo della provocazione. Lui, Hujar, no. Il suo lavoro, rivolto direttamente ai protagonisti di una comunità che da lì a poco sarebbe stata travolta dalle conseguenze dell’Aids, di cui egli stesso fu vittima, mostra l’evidenza di una empatia che sa di una discesa profonda nell’abisso identitario. I volti maschili, i corpi nudi, le drag queen come i clown, colti in una dimensione privata, antecedente cioè all’atto di “mostrarsi” richiamano a un desiderio di connessione, a una specie di disvelamento di un capitolo delle attività umane relegate al margine e la cui esistenza può solo legittimarsi nella dimensione spettacolare, nel girone in cui anche la trasgressione è ridotta a dimensione folclorica. I soggetti di Hujar hanno una accentazione per così dire umanistica, niente a che vedere con Mapplethorpe: qui, nelle fotografie di Hujar non c’è il desiderio di sopraffarci con gli strumenti dello stupore né intendono procurarci sgomento – premesso che dagli anni Settanta ad adesso abbiamo visto praticamente di tutto – piuttosto è viva l’intenzione di narrare, vocazione insita nell’ontologia della fotografia, il mondo obliquo e trasversale di una comunità d’uomini protagonisti di un conflitto profondo. Peter Hujar, si è detto, non conosceva il termine “compromesso”, condizione che lo avrebbe guidato verso scelte radicali quanto distruttive, eppure in questo vogliamo intravvedere una purezza d’intenti anti-istituzionale pagata con l’esclusione dal consesso fotografico imperante. Eppure la liberazione dal desiderio, l’ottenimento della notorietà ha fatto di lui un uomo libero. Consapevolmente libero. “Portraits in Life and Death” è un esordio e insieme una fine, una pubblicazione che porta in sé i segni di un destino già indossati da altri autori. Disse: “Devo morire perché la mia opera sia conosciuta e apprezzata”. E’ accaduto proprio così, la lenta carburazione del suo successo, il riconoscimento che merita spiegano molte cose. Non di lui, d’un mercato che si autoalimenta di voci omologate.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

da “Portraits in Life and Death”

foto Peter Hujar

1976, "Portraits in Life and Death" comes out. An unusual book, a masterful sequence of portraits is followed by a series of images of mummies kept in Palermo, in the catacombs of the Convento dei Cappuccini, the destination of many American photographers who go there with the same approach as the Grand Tour. Maybe that's why that in the preface to the book Susan Sontag writes "Photography transforms the whole world into a cemeteries", prefiguring one of the key themes of Barthes' work.

Peter Hujar (1934-1987) is the talented American photographer, as well as unrecognized, and is considered one of the most influential photographers of the end of the 20th century in the sector. Shy, reserved and coherent Hujar did not like compromises nor did he ever have a working relationship with gallery owners and collectors. It could be called an outsider, but Hujar managed to influence the work of many famous colleagues who found inspiration in his photographs.

But the influences end here, so the tributes of Goldin and Mapplethorpe are sent back to the sender without compliments and with the invitation of Hujar not to be cited as an inspiring source. To Nan Goldin he reproached certain commercial drifts, to the wink to a self-referential mannerism; worse he went to Mapplethorpe, accused of showing himself too interested in the construction of an adoring public, and that the desire to enter museums had evaporated the subversive scope of the first photographs to found a kind of neo-classicism of provocation.

He, Hujar, no. His work, aimed directly at the protagonists of a community that would soon be overwhelmed by the consequences of AIDS, of which he himself was a victim, shows the evidence of an empathy that knows of a deep descent into the identity abyss. The male faces, the naked bodies, the drag queens like the clowns, caught in a private dimension, that is before they "show" themselves, recall a desire for connection, a kind of unveiling of a chapter of human activities relegated to the margin and whose existence can only legitimize itself in the spectacular dimension, in the group in which even the transgression is reduced to a folkloric dimension.

Hujar's subjects have a so-called humanistic accentuation, nothing to do with Mapplethorpe: here, in Hujar's photographs there is no desire to overwhelm us with the tools of amazement nor do they intend to procure dismay - given that from the Seventies to the present we have seen practically everything - rather the intention to narrate is alive, a vocation inherent in the ontology of photography, the oblique and transverse world of a community of men protagonists of a profound conflict.

Peter Hujar, it has been said, did not know the term "compromise", a condition that would have guided him towards radical and destructive choices, yet in this we want to glimpse a purity of anti-institutional intent paid with the exclusion from the prevailing photographic assembly. Yet liberation from desire, the attainment of notoriety has made him a free man. Consciously free. "Portraits in Life and Death" is both a debut and an end, a publication that carries within it the signs of a destiny already worn by other authors. He said: "I must die so that my work is known and appreciated". This is exactly what happened, the slow development of its success, the recognition it deserves explain many things. Not of him, of a market that feeds on approved items.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

da “Portraits in Life and Death”

foto Peter Hujar