FOTOTECA SIRACUSANA

PHOTOGALLERY - FOTOGRAFIA VINTAGE - BIBLIOTECA TEMATICA - CAMERA OSCURA B&W - DIDATTICA

SCRIPTPHOTOGRAPHY

William GEDNEY (USA)

WILLIAM GEDNEY

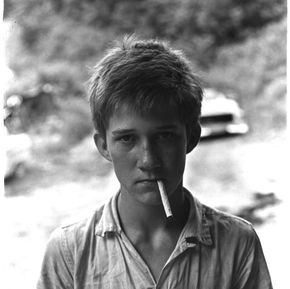

“Ogni famiglia infelice”, recita l’incipit di un caposaldo della letteratura mondiale, “è infelice a modo suo” e se perdi il lavoro quando hai dodici bocche da sfamare l’infelicità si arricchisce di nuove profondità. Kentucky, 1962. Un giovane che intende farsi largo nella fotografia ha quanto basta nelle tasche per intraprendere un viaggio nelle viscere di un’America sconosciuta, distante da quel sogno americano confezionato per blandire chiunque, ma che molto più spesso si trasforma in un incubo senza risveglio. Lui, il giovane fotografo è William Gedney (1932-1989); loro, la famiglia entrata nell’incubo della povertà, sono i Cornetts. Hanno tutti qualcosa in comune, come la sensazione d’essere in qualche maniera degli esclusi: Gedney sconta vivendo sulla sua pelle la difficoltà di dichiararsi omosessuale – condizione che terrà nascosta per sempre ai suoi familiari – a cui si unirà, più tardi, la preoccupazione che il suo lavoro non ricevesse l’attenzione che meritava, mentre i Cornetts sperimentavano sulla loro pelle gli effetti di una recessione economica che avrebbe stravolto l’esistenza. Il progetto che ne verrà fuori, “Kentucky”, traccia lo stabilirsi di una profonda intimità umana, una fusione così stretta che Willie, il capofamiglia, affermò in seguito di ‘sentire’ Gedney come parte della sua stessa famiglia. La ragione è evidente ed è presente alla visione di ogni singola fotografia: Gedney non sta fotografando la povertà, ma ritrae una famiglia impegnata a sopravvivere e che si sostiene con la fierezza dell’orgoglio. Siamo, per certi versi, in una direzione diametralmente opposta alle intenzioni con cui la Farm Security Administration aveva sguinzagliato nell’America rurale i migliori fotografi perché ne censissero le condizioni. Lì, in quel caso, c’era un versante antropologico da mettere a registro, una povertà da trasformare in numeri da statistica. In “Kentucky” c’è la discesa nella meravigliosa intimità di un nucleo familiare la cui derelitta gioiosità diviene strumento, un’arma da contrapporre a un destino su cui non si ha controllo. Nelle fotografie di “Kentucky” (Gedney si recherà ancora dai Cornetts nel 1972 per completare la serie) c’è come un segreto e ossessivo incantesimo, una rilassata malinconia che riempie il giorno, accarezzandolo dolcemente come una forma di resiliente distacco. Tutte le fotografie, compresi i ritratti, ci appaiono portatrici di una silenziosa complicità tra il fotografo e i soggetti, segno che Gedney si muovesse con la naturalezza che proviene dall’aver stabilito tra le parti una profonda complicità. Non sorprende dunque se a volte sembra che non accada nulla: in quella quotidianità è racchiuso lo spessore di un ingresso altrimenti precluso in assenza di fiducia: i ragazzi che armeggiano nel motore di un’automobile; la rilassatezza di una pausa nella veranda; bambine che tengono in braccio sorelline più piccole; adolescenti alle prese con una sigaretta sono momenti di crudo verismo, qualcosa da testimoniare senza alcuna necessità di porre filtri né di abbellire con espedienti estetici: tutto è lì, materia vergine e al fotografo non resta che coglierne i momenti, mentre noi che osserviamo i Cornetts li vediamo ben oltre la loro corporeità, quasi che Gedney avesse utilizzato uno strumento per vedere oltre ciò che è visibile nella vita delle persone. William Gedney tocca il nervo più sensibile ed empatico della nostra attenzione. Con lui il reportage documentaristico si arricchisce di note che risuonano d’umanità, mentre attendiamo che al fotografo spetti la considerazione che merita.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

da “Kentucky”

foto William Gedney

"Each unhappy family", says the beginning of a milestone of world literature, "is unhappy in its own way" and if you lose your job when you have twelve mouths to feed unhappiness it is enriched with new depths. Kentucky, 1962.

A young man who intends to make his way in photography has enough in his pockets to embark on a journey into the bowels of an unknown America, far from that American dream made to blandish anyone, but which much more often turns into a nightmare without awakening. He, the young photographer is William Gedney (1932-1989);

they, the family that entered the nightmare of poverty, are the Cornetts. They all have something in common, like the feeling of being in some way excluded: Gedney suffers from living on his skin the difficulty of declaring himself homosexual - a condition that he will keep hidden from his family forever - to which he will join, later, the concern that his work did not receive the attention it deserved, while the Cornetts experienced on their skin the effects of an economic recession that would have upset the existence.

The resulting project, "Kentucky", traces the establishment of a profound human intimacy, a fusion so close that Willie, the head of the family, later claimed to "feel" Gedney as part of his own family. The reason is obvious and is present at the vision of every single photograph: Gedney is not photographing poverty, but portrays a family committed to surviving and supporting itself with the pride of pride.

We are, in some ways, in a direction diametrically opposed to the intentions with which the Farm Security Administration unleashed the best photographers in rural America to censor the conditions. There, in that case, there was an anthropological side to register, a poverty to transform into statistics numbers. In "Kentucky" there is the descent into the marvelous intimacy of a family whose derelict joy becomes an instrument, a weapon to contrast with a destiny that is beyond control.

In the photographs of "Kentucky" (Gedney will still go to Cornetts in 1972 to complete the series) there is a secret and obsessive spell, a relaxed melancholy that fills the day, gently caressing it as a form of resilient detachment. All the photographs, including the portraits, appear to be the bearers of a silent complicity between the photographer and the subjects, a sign that Gedney moved with the naturalness that comes from having established a deep complicity between the subjects.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that at times it seems that nothing happens: in that everyday life the thickness of an otherwise precluded entrance without trust is enclosed: the boys who fumble in the engine of a car; the relaxation of a break on the veranda; little girls holding smaller sisters in their arms; teenagers grappling with a cigarette are moments of raw realism, something to testify without any need to put filters or embellish with aesthetic expedients: everything is there, virgin matter and the photographer can only grasp the moments, while we who observe the Cornetts we see them far beyond their corporeality, almost as if Gedney had used a tool to see beyond what is visible in people's lives. William Gedney touches the most sensitive and empathic nerve of our attention. With him the documentary reportage is enriched with notes that resonate with humanity, while we wait for the photographer to have the consideration he deserves.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

from “Kentucky”

ph William Gedney